Writers usually fall into one of two categories: the plotter or the pantser.

Plotters prefer to plan out every aspect of their stories ahead of time, from the setting, character, theme, structure. They will plot out every scene from the opening paragraph to the final resolution. They have to know every detail in advance before starting to write. Plotting allows writers to view their story from all detailed angles. They know exactly what they want to write before writing it.

I’ve tried this plotting approach once before early in my fiction writing. It was the first story I attempted to write. I quickly gave up on it because I found it limiting. My plotting didn’t allow for new characters to show up, and I struggled to find the right place in the story for new scenes as I thought of them.

Still there are plenty of authors who have plotted their way to success. Fantasy author K.M. Weiland is a big proponent of outlining and story structure, and goes into a deep dive on these subjects on her blog. She’s also written several books about plotting if you want to learn more.

One disadvantage I see is the extra time it takes to get the details “just right.” It can take the wind out of your creative sails too. By the time you’re done plotting, you could lose interest in your story because you feel you’ve already written it in plotting form.

But not every writer works that way.

Then there are the pantsers . . .

I always believed I was a pantser, also known as a discovery writer, because I enjoyed discovering my story as I wrote. With only a vague sense of main characters and a few scene ideas, pantsers tend to begin writing if only to see where the story takes them, or whether there’s a story at all.

The advantage of writing by the “seat of your pants” is that it gives the imagination free rein. The story, without the limits of plotting, can go in a multitude of directions, and it can be fun to discover new characters and settings that you didn’t think of initially. Writers feel free to explore their story world without the limitations of a set of rules or structure.

The downside, however, is that by the end of the drafting phase, what writers have is a ton of material with no cohesiveness between scenes, characters or plot. That only makes the editing phase much harder because there’s so much material to dig through, and much of it will land on the cutting room floor anyway. As I quickly learned, pantsers usually have to do several rewrites to get the story to where you want it to be, which can be a drain on time and energy, not to mention patience.

What if you’re neither a pantser nor a plotter – or you’re a little of both?

While I’ve experimented with both of these approaches, I realized that I don’t fit neatly in either one. While I love exploring plots and characters organically, I also recognize that I need to plot my story to some extent so I know where it’s going. Otherwise, I’m only spinning my wheels, editing and rewriting sections until they feel right.

Enter Puzzling.

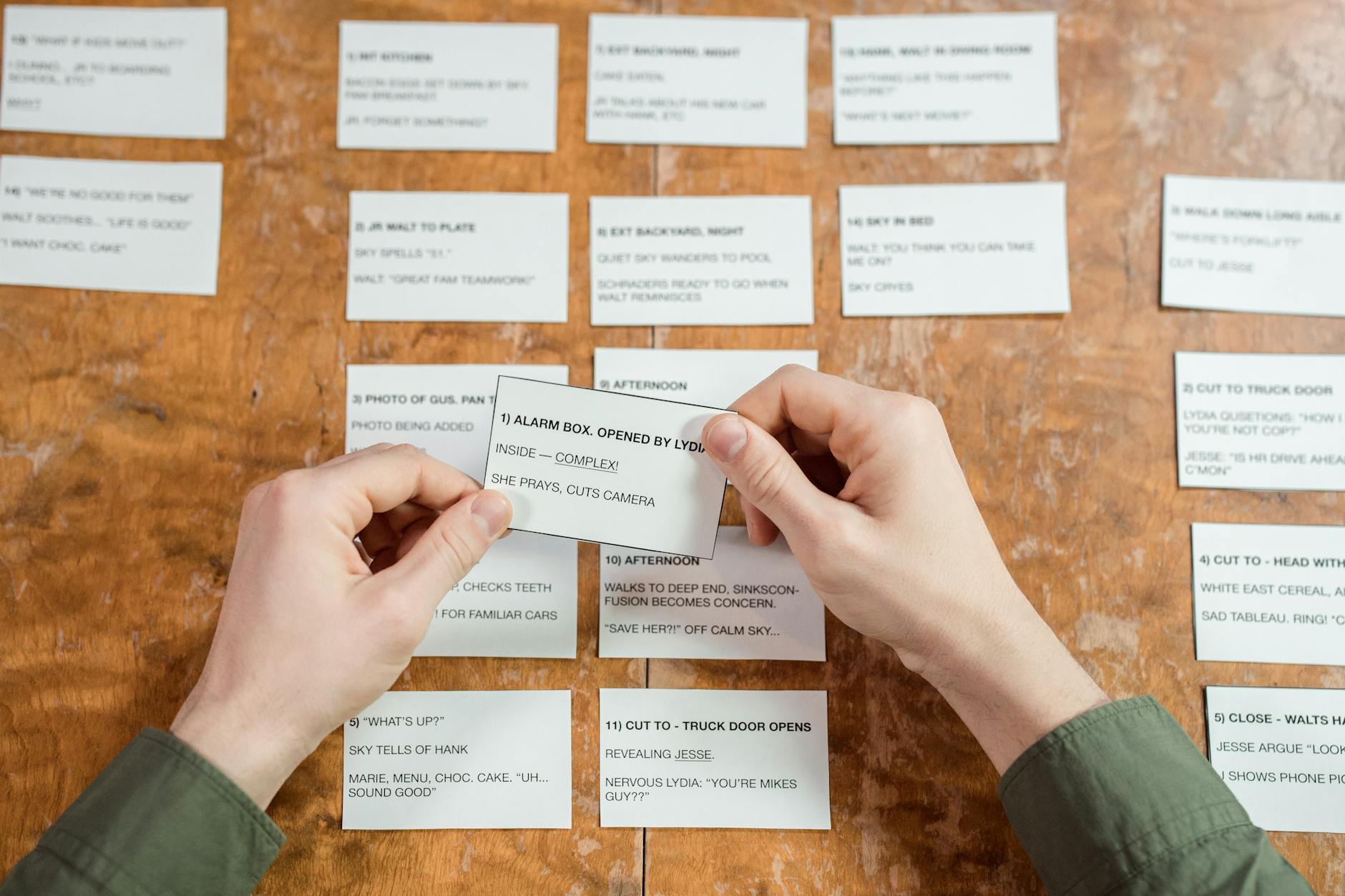

The Novel Smithy Lewis Jorstad explains that puzzling works by bringing elements of plotting and pantsing together. For example, perhaps you have a brilliant story concept and can visualize several scenes in your mind, have a rough idea of characters and an inkling of how it will end. Using index cards or post-it notes, jot down each individual scene – one idea per card. You may not think of every scene right off the bat. You may only have three or four scenes to start. But that’s okay. What you are doing is creating a puzzle with various pieces that will eventually fit together. This is the discovery part.

Once you have a collection of scenes on index cards (or post-it notes), spread them all out on a table or tape to the wall so you can see them all at a glance. Then rearrange them in the order you think they should go. This is the plotting aspect.

Once the cards are in some story order, review them again. Note if there are any gaps in the sequence. Wherever there is a gap, insert a card indicating a scene to come.

The advantage to puzzling is that it allows you to generate scenes on the go. You don’t have to think of every scene before writing. You can write the scenes you do know, knowing the rest will come eventually. You don’t have to follow any structural rules.

Even while drafting, you may still come up with new scenes. When that happens, jot them down on a card and insert them where you think they might fit in the story. You can add or delete scenes and change the order of them as you go along. It gives you more control and flexibility than a straight plotting structure, which can be limiting to those who want to give their imagination free rein.

Another benefit is the ability to review your story at a glance scene-by-scene and make adjustments to the timeline. You can also identify which scenes are the key plot points of your novel. I suspect this approach results in fewer rewrites.

Are there any downsides? So far, I haven’t found any, though I just started working with it for my current work in progress. In the short time I’ve been using this puzzler approach, I’ve learned a few things:

- It has helped me maintain my interest in the story. With previous approaches, I’ve invariably lost interest in my manuscript and given up on it, or got lost in the muddling middle.

- It allows me to assess my scene sequence and rearrange them as I see fit, without having to rewrite anything.

- It helps me stay focused on one scene at a time. With one scene per card, I know what I’m writing next and I’m not left staring at a blank screen. The cards give me a clue and keep me on track.

If you’ve tried plotting or pantsing, and they haven’t provided the results you want, give puzzling a try. You may find that being a puzzler makes you a more productive writer.