No doubt you’ve heard about the importance of the firsts in writing—the first line, the first paragraph, the first page, the first scene, the first draft. Each “first” has its own role to perform. It must contain certain elements for the story to work, just like pieces of a giant puzzle. Every element must fit together.

Why are they important? How can you make them as compelling as possible so your manuscript doesn’t end up in the editor’s slush pile? Here’s what you need to know about each of these “firsts” to readers, agents and editors won’t stop reading.

The first line

There is some debate about the importance of the opening sentence. Some say it has to grab the reader from the get-go and hint at the conflict to come. Others say it’s more important to focus on the first paragraph which gives readers more information about what’s to come.

“The first sentence alone doesn’t give readers enough information or the writer enough room. The paragraph gives enough room and direction to write your book,” says John Matthew Fox in a guest post on JaneFriedman.com.

I’m inclined to agree with Fox. I’ve read a few doozies of opening lines for some wonderful stories, but most of the time, opening lines are rather lackluster. I still kept reading anyway, and the stories were just as readable.

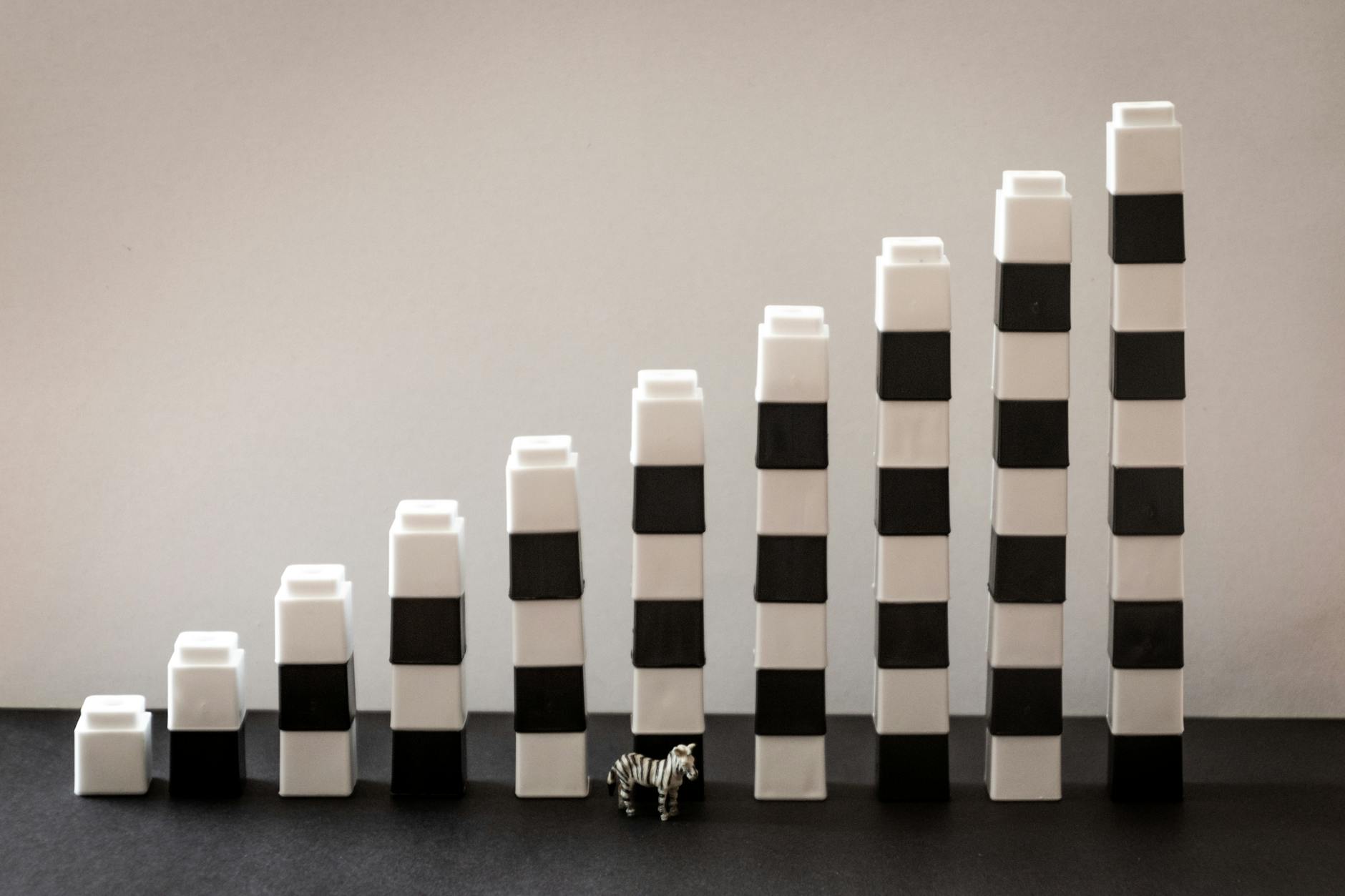

I see the first sentence as the first blow of a balloon. You won’t see much result from your effort of blowing, but with sustained effort, that first line serves as the starting point for something bigger.

The first paragraph

The first paragraph should make a strong first impression, stronger even than the first line. It should give readers enough information about the story to decide if they want to keep reading.

John Matthew Fox says opening paragraphs contain four critical elements:

- Characterization – Readers need to learn something about the main character. It could be a dilemma they’re grappling with, some deep emotion they’re feeling or some puzzle they’re trying to solve. Readers need to know something about them that makes them relate to the character, or makes them want to root for them in the story.

- Energy/tone – The first paragraph should bring a certain energy to the story. A rom-com, for example, will be written with a light-hearted tone, while a horror story might have a darker, creepier tone

- Mystery or conflict – The opening paragraph should hint at some question or conflict that needs to be resolved. For example, why a complete stranger is watching someone else from a distance.

- Emotion – Finally, the first paragraph should exude some emotion to hook the reader, whether that’s fear, grief or disappointment.

The first page

At an average length of 250 to 300 words, the opening page has to do a lot of things in a short amount of time to kick the story into high gear. It’s the heavy lifter of all the firsts.

In a recent weekly newsletter, Karyn Fischer of Story & Prose outlines the common elements of the first page.

* Character and desire – What does the character want? The first paragraph might have hinted at this, but the opening page goes into more depth.

* Conflict and stakes – What or who opposes the main character in getting what they want? * Voice – Fischer says it’s often difficult to pinpoint voice, but you might detect it through the way they speak or think. Does their voice sound true to life?

*Setting and world-building – The first page should give readers a sense of where they are in the story. Perhaps it’s a birthday party in someone’s home, the site of a car accident or a courtroom. Don’t overload the story with setting details, but sprinkle them throughout to give a sense of time and place.

* Action – Make sure the character is doing something, whether it’s baking a cake or being chased by thieves.

* Genre – Depending on the genre, the opening page should hint at the type of story people are reading. In historical fiction, for example, the first page might have visual cues that show time and place.

First scene/first chapter

I’ve combined the first scene and chapter into one section for a couple of reasons. First, they consist of the same elements and strive to accomplish the same goals. Second, a chapter may consist of a single scene, or several.

While the first page does a lot of work to prepare readers for what’s next in the story, the first scene or chapter ramps up the effort. In addition to doing what the first page does, the first scene or chapter does more, such as:

* Introduce other compelling characters that will either support or antagonize the main character.

* It grounds the reader into the story, providing more details about what the protagonist is dealing with.

* It continues to build on the tone established in the first page.

* It provides the hook that will keep readers turning the page.

* Depending on the story, the first chapter (not necessarily the first scene) should contain the inciting incident, the situation that gets the story moving.

By the end of the first scene or chapter, readers should know enough about the main character and their plight to determine if they like the character and empathize with their situation. If readers don’t find anything to like about the character, it’s likely they’ll give up on the story.

First 50 pages

The first 50 pages are important because it’s those pages that many editors and agents will review to determine if it’s worth reading—and publishing. It’s also a litmus test for readers. If the story loses its steam, readers will lose interest before they get to that 50-page mark. More specifically, the first 50 pages:

* Give readers, agents and editors an impression of your writing style.

* Includes the inciting incident and shows the raising of the stakes

* Shows the initial progress in the protagonist’s character arc. How will they grow or progress as the story moves forward?

First draft

When you finish writing your first draft, you might think your work is done. But it’s only just starting. The editing and rewriting process is where the real creativity begins, experts suggest.

The first draft, in all its messy glory, should contain the spine of the story—namely the who, what, when, where, why and how. It has three main goals:

* Helps you get all your ideas down on paper, from characters and their backstory to setting and dialogue.

* It helps you lay out the major plot points.

* It provides a road map for how to proceed during the revision process.

If all goes well at each of these “first” elements, then it’s only a matter of time before you enjoy the next first in your professional writing life—publishing your first book.