Whether you’ve been a writer for some time or you’re just starting out on your writing journey, you likely have heard about National Novel Writing Month, which takes place every November. While the organization that started this event has shut down, the mission still holds true: to encourage writers of all levels of experience to amp up their productivity. The aim is to write 50,000 words during the month, or approximately 1,666 words per day.

That’s a hefty load for any writer. It’s much like aiming to walk 10,000 steps that doctors recommend (or about five miles). Who has time to do that? Both activities require more time than most people have available to them.

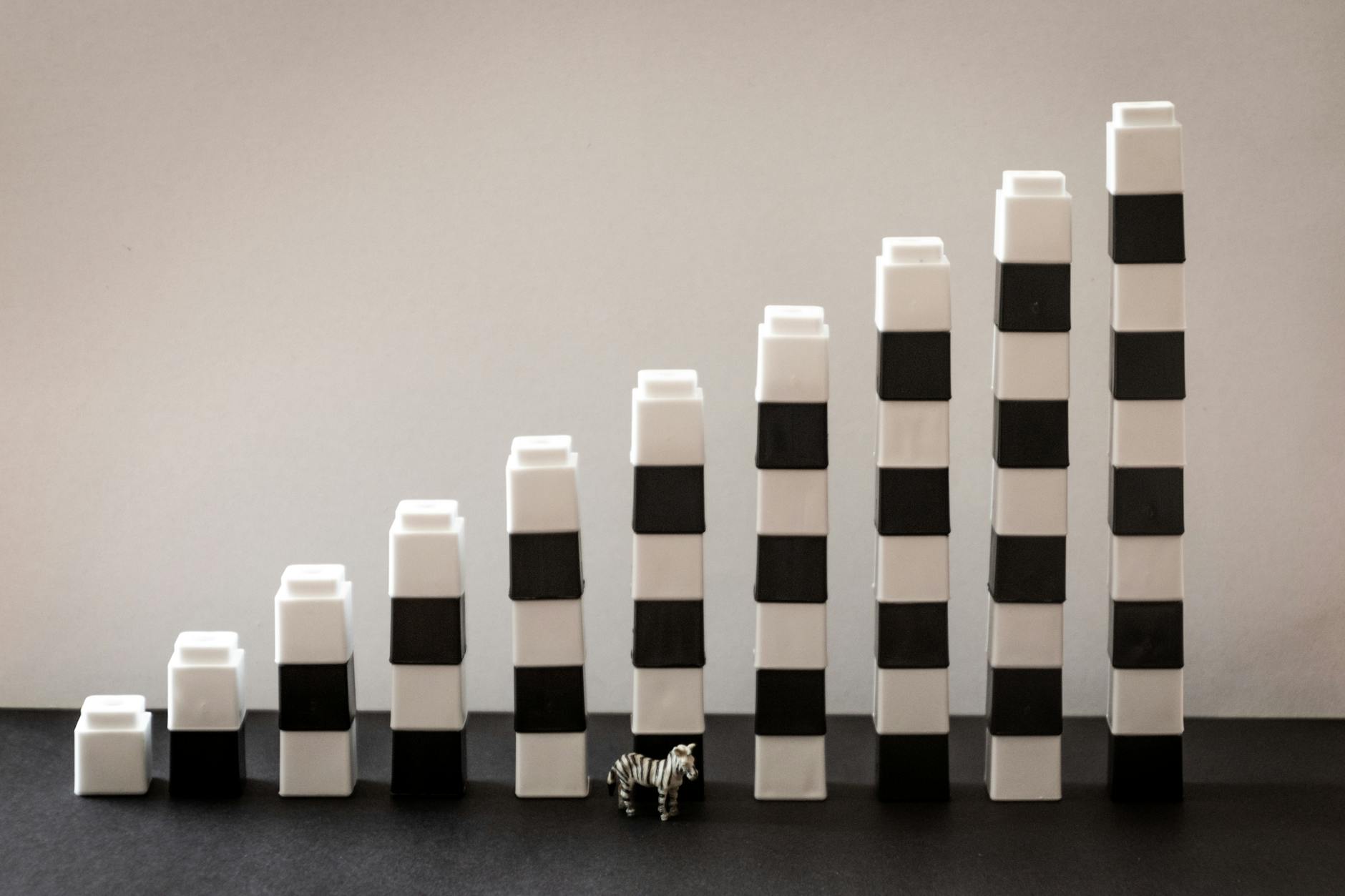

The way I see it, the November Writing Challenge can be about any goal you want to achieve. It doesn’t have to be about 50,000 words if that goal is too steep. The Challenge is about finding new ways to fit writing into your life, whether that’s writing for one hour per day or writing only 500 words per week. It’s about stretching yourself beyond what you’re used to doing in your writing life. Plus it just feels better knowing other people are going through the challenge too. There’s power in numbers, and it’s empowering when you know you’ve got other writers beside you. Remember, the November Writing Challenge is whatever you want it to be.

Several writing communities offer their own writing challenges and support systems for writers. For example, Story Forge’s challenge is 30,000 words, or about 1000 words per day. That’s a more accessible goal for many people. You can find quite a few others like Reedsy, ProWriting Aid and AutoCrit.

No matter which challenge you follow or if you make up your own like I’m doing, the key point to remember is to stretch yourself. Aim for more words. Longer writing periods. Or do something different. Consider these other possibilities:

* Draft one flash fiction story (about 1500 words) or a short story (up to 15,000 words) per week

* Commit to writing 500 words per day, the equivalent of two pages.

* Write for 30 minutes per day, especially if you’re used to writing sporadically.

* Write your current work-in-progress from a different character’s point of view.

* Write in a different genre than you’re used to. If you’re used to writing fiction, try writing essays.

You might consider some non-writing activities too.

* Read the first draft of your current work-in-progress, noting changes you want to make in the margins. But don’t make the changes just yet.

* Read about the writing craft. If you’re new to writing, this might be a good time to become familiar with the tools you need to craft your story. Learn about plotting, story structure, character development, conflict, etc.

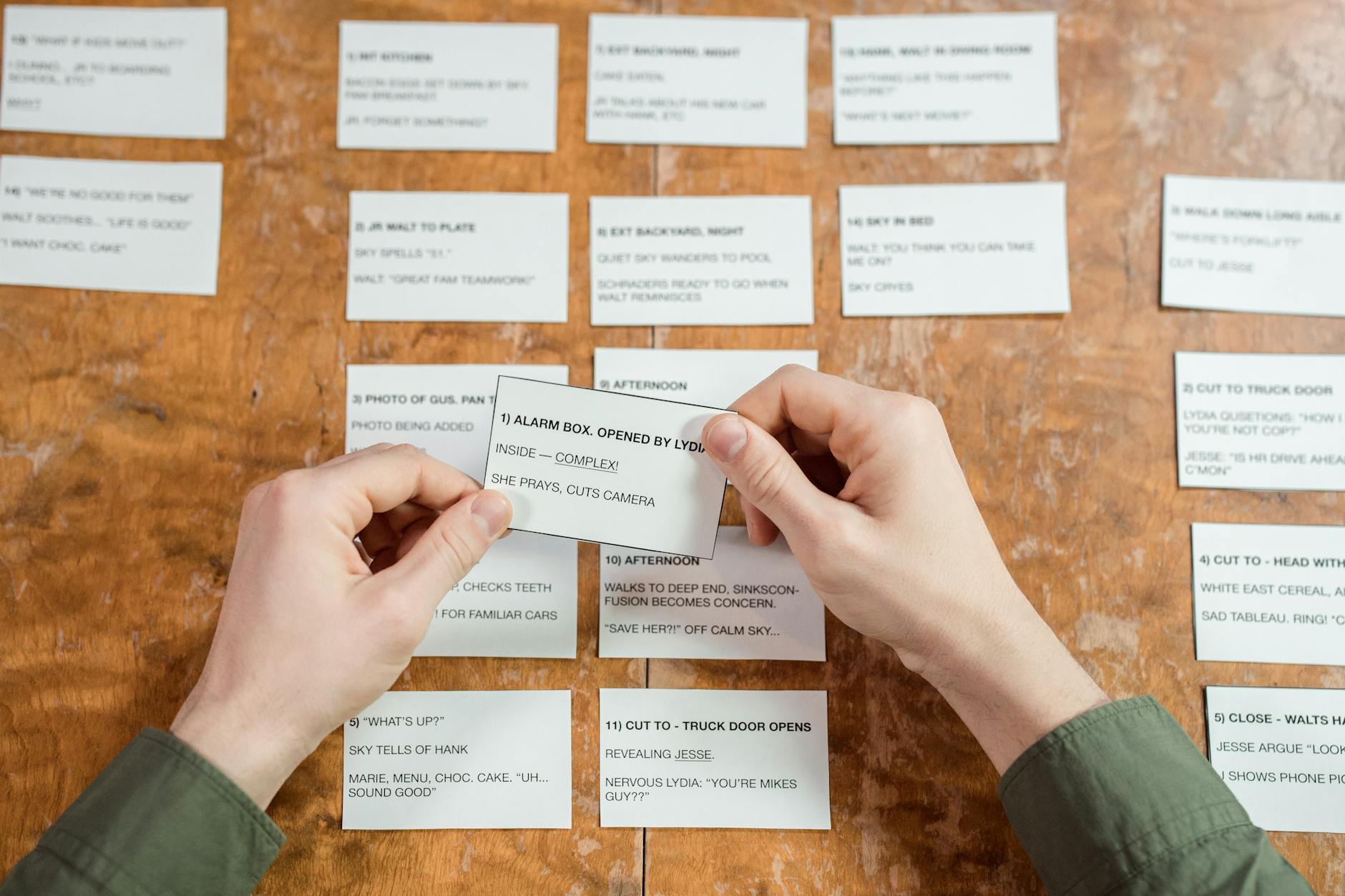

* Got a story dancing in your head? Sketch out several scenes to get your creative juices flowing.

* Do background research. Is there a subject you know nothing about but is imperative to your current project? Spend a few minutes each day researching that topic.

* Spend some time world-building. What do the settings in your story look like? Whether you’re writing a fantasy in a make-believe world or a mystery set in a small town, take time to convert the setting from your imagination to the paper or screen.

* Work on character development. Get to know your characters by writing profiles of the main ones. Describe more than their appearance, but their desires, their personality quirks, their strengths and weaknesses.

The beauty of the November Writing Challenge is to make it whatever you want it to be depending on your goals and what you’re working on. You set the goals and how you’ll measure your success. Just remember to ramp up the activity so you’re challenging yourself to do something different or to improve your productivity.

For example, I plan on using November to draft a holiday romance novella. I’m already prepping by sketching out scenes I plan to write later. My goal is to draft five pages per day, or roughly 1000-1,2000 words. If all goes well, my rough draft should be complete by the end of the month.

If you’re creating your own challenge, it might be helpful to follow these basic rules:

* Establish your goal for November. What do you want to accomplish by month’s end?

* Make sure your goal is measurable. How do you know you’ve achieved success? Set a specific time limit or number. For example, aiming to write 1000 words per day or writing for 15 minutes before bedtime.

* Track your progress. Using a calendar, mark a symbol or star on the days you write or jot down how many words/pages you finished.

* Be sure to ramp up the difficulty. If you’re used to writing three days a week, what can you do to increase that output to five days?

* Reward yourself. When November ends and you can see the progress you’ve made, celebrate your accomplishments. Perhaps treat yourself to a low-cost writing webinar or a book about the writing craft.

You don’t have to target 50,000 words to be successful during November Writing Month. Whether you commit to writing one page per day or 1000 words per day, simply by sitting down to write, you’ve already achieved success.